We are on our second day of the triduum. Today’s liturgy is called Good Friday of the Lord’s Passion. We don’t have a mass today. Instead, we have a liturgy which is made up of three parts: the Liturgy of the Word at which the Passion of Christ according to St. John is proclaimed and which ends with the Solemn Intercessions, the Adoration of the Holy Cross and Holy Communion.

Yes, this is the only day throughout the year where the church does not celebrate the Eucharist. There is also no wedding, baptism, confirmation and certainly no ordination. In fact, there are only two sacraments that are offered on this day: Reconciliation and the Anointing of the Sick. These sacraments truly underscore the meaning of this day and point to the reason why we call this Friday good: We call this Good Friday because it is a day of renewal, forgiveness and reconciliation.

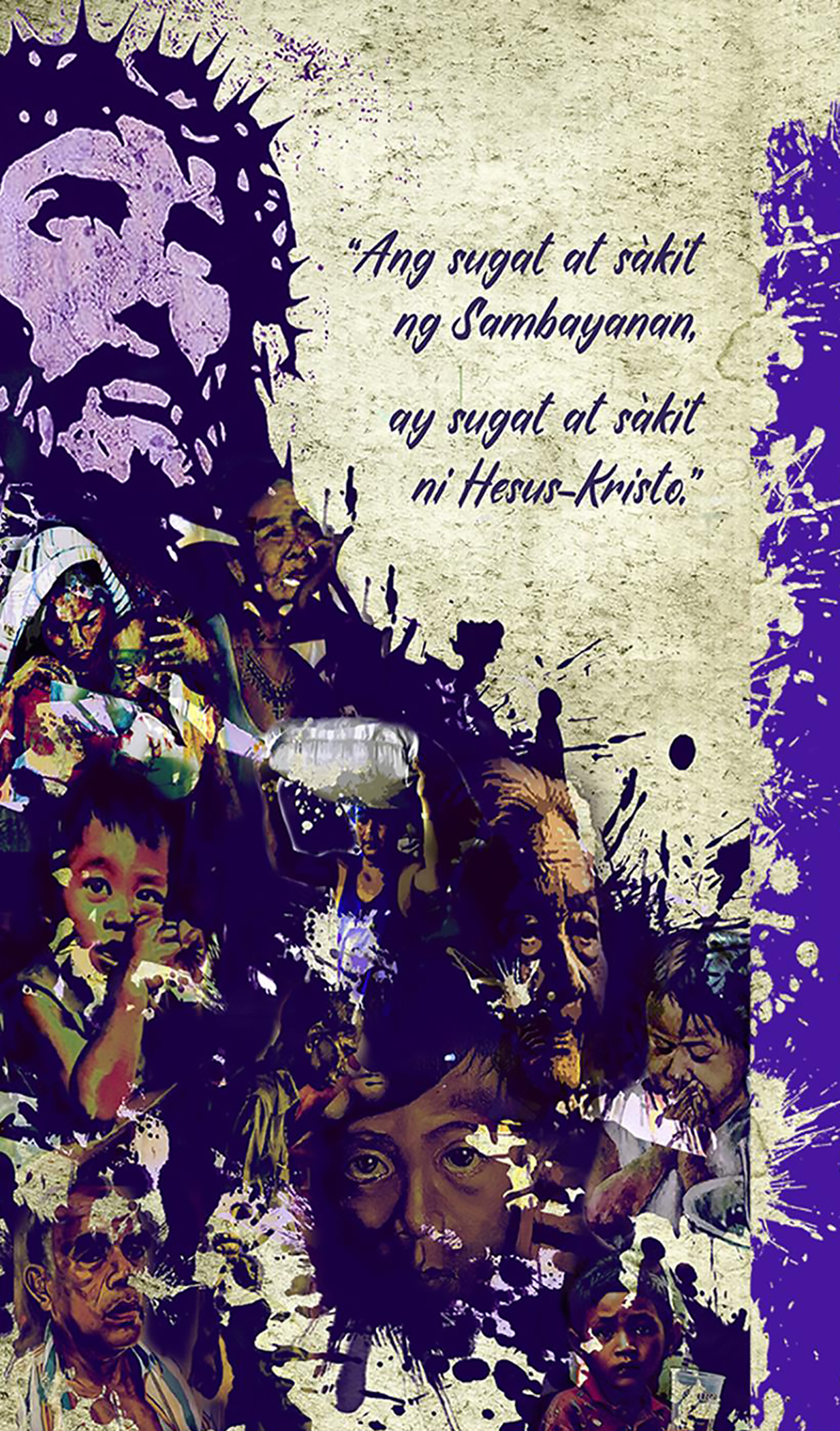

Good Friday is a day of paradoxes. All four gospels openly tell of the passion of Jesus as a story of contradictions. It depicts Jesus proclaimed as king with a crown of thorns, a staff and clothed in a purple cloak. The soldiers spat on him and struck him on the head with the staff repeatedly. The people who shouted hosanna to our king when Jesus entered Jerusalem just a few days ago are the same people who shouted “Crucify him!” and elected Barabas to be released on the day of Passover. The greatest of these ironies is the cross. Jesus on the cross with the sign “Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews,” died of a slow, painful, excruciating, gruesome, and humiliating death.

Franciscan Fr. Ron Rolheiser says that we tend to misunderstand “the passion of Jesus”. Spontaneously we think of it as the pain of the physical sufferings he endured on the road to his death. We are not helped by gruesome cultural depiction of Jesus’ passion like Mel Gibson’s film, “The Passion of the Christ.” This is also reinforced by our own Good Friday observances like the carrying of wooden crosses, crawling on rough pavement, self-flagellation and the re-enactment of actual crucifixion like the one in San Pedro Cutud, San Fernando, Pampanga.

This is not to downplay the brutality of Jesus’ pain but Rollheiser explains that what the evangelists focus on is not the scourging, the whips, the ropes, the nails, and the physical pain. They emphasize rather that, in all of this, Jesus is alone, misunderstood, lonely, isolated, without support, unanimity-minus-one. What’s emphasized is his suffering as a lover; the agony of a heart that’s ultra-sensitive, gentle, loving, understanding, warm, inviting, and hungry to embrace everyone but which instead finds itself misunderstood, alone, isolated, hated, brutalized, facing murder..[1] Think of the experience of dying covid-19 patients. Most of them die in isolation at the intensive care unit. Their families couldn’t go in and touch him or hold their hands. After they die, they are immediately cremated. It must have been so tragically sad.

Despite the brutality of the suffering and death of Jesus, however, the gospel of John portrays Jesus as victorious and in control of the whole situation. Franciscan Fr. John Boyd-Boland explains that John’s Jesus longs for the cup of suffering; he is determined to drink the “cup” of his death because this act is the ultimate in love, and reveals God’s love for us all. Then in his confrontation with Pilate, Jesus stands totally in command of the situation and Annas is left bewildered and confused. Having been struck on the face by the Temple police, Jesus is left totally composed after the incident. He replies that his teaching has always been open and explicit, “My kingdom is not of this world.” Here the prisoner interrogates his interrogator! Finally, upon the Calvary cross, Jesus dies with majestic assurance.

In openly depicting Jesus’ passion, suffering and death, are not the evangelists actually proclaiming that in a world of hatred, violence, and falsehood, truth, love, and goodness reigns? By showing Jesus’ resoluteness and benevolence up to the end, are not the evangelists decrying the travesty of worldly powers and pretentious kings instead? Could we have missed the greatest irony which the evangelists have employed?

We live in a world today not much different from the world when Jesus lived—a world full of contradictions and sufferings: Innocent and good people continue to suffer, the gap between the rich and the poor continue to widen, there is plenty of innocent killings, gender and racial discrimination continues, poverty and violence reigns. In the midst of the contradictions and suffering, the temptation is to go low and become like the worldly powers that supports and preserves these contradictions—violent, tyrannical, prejudiced, vindictive, manipulative and deceitful.

Following Jesus example, we need to embrace these paradoxes while standing true to ourselves. Sometimes we need to accept opposition to choose community; sometimes we need to accept bitter pain to choose health; sometimes we need to accept a fearful free-fall to choose safety; and sometimes we need to accept death in order to choose life. If we let fear stop us from doing these, our lives will never be whole again.

This is what Jesus has accomplished when he proclaimed in his last words in the gospel: “It is finished.” Jesus leads us to love, forgiveness, compassion and reconciliation despite the violence and brutality around him. God’s way is integration, reconciliation and communion. By his dying, Jesus reconciled once again heaven and earth.

As St. Paul proclaims,

“God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise;

God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong;

God chose what is low and despised in the world, things that are not,

to reduce to nothing things that are” (I Cor 1: 27 – 28).

Yes, ironically but perfectly, liberation is accomplished through God’s death. Liberation is accomplished through Jesus’ death on the cross.

[1]Ron Rolheiser, OMI, The Agony in the Garden – The Special Place of Loneliness, February 22, 2004. Accessed 16/03/18 at http://ronrolheiser.com/the-agony-in-the-garden-the-special-place-of-loneliness/#.WqsieUxuI2w